Temporomandibular dysfunction: energy patterns for acupuncture treatment

Introduction

For traditional Chinese medicine, diseases classified by Western medicine are important signs to reach an energy diagnosis, as they inform clinical symptoms and signs so that the acupuncturist can act in a way directed at the root of the problem, that is: what is the energy syndrome because a syndrome represents a set of symptoms that affect the organism during the pathological process (1).

In this study, the “disease” we will address is temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) which is “a set of clinical signs and symptoms involving the masticatory muscles, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and associated structures” (2).

TMD are defined as a set of painful changes that affect the TMJ and masticatory muscles (3). According to epidemiological data, in every 3 patients with joint problems, 2 are women (4). In TMD, the most common symptom is related to muscle pain during chewing, and studies report that muscle sensitivity to palpation is greater in women when compared to men (5), negatively affecting the patient’s quality of life (6,7).

Pain associated with TMD is the third most prevalent chronic pain condition worldwide, after tension headaches and back pain (8), with muscle fatigue and facial pain TMJ and/or masticatory muscles, pain in the head and ear, limitation and/or deviation of mandibular movements being the most frequent symptoms (9).

The highest prevalence of TMD is observed in adults (31.1%) with a peak of occurrence between 30 and 40 years of age and a lower occurrence in children and adolescents (11.3%) (10). A review of 18 epidemiological studies ranges from 16% to 59%, with the prevalence of pain related to TMD in the Brazilian population being 25.6% (11).

TMD affects one of the most complex joints in human beings, which is the TMJ, and whose etiology is multifactorial, from stress to physical traumatic factors, making a multidisciplinary approach important. The therapeutic approach by Western medicine is made with analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy, occlusal splint, and surgery, among other approaches (12).

As a therapeutic approach, acupuncture stands out for not being invasive and presenting effective results, as reported in systematic review studies (13-16). Treatment for TMD can be performed in combination with therapies such as dry needling and plaque, plaque, and anti-inflammatory drugs (17).

La Touche et al. (13) in a systematic review from 1997 to 2007, selected 4 RTC of patients with muscle TMD and found effectiveness of acupuncture with short-term analgesic effects and suggests that more studies be carried out to find which acupoints and best combination of acupoints for the management of TMD.

Garbelotti et al. (14) in a review of 34 articles (1983 to 2015), whose most used acupoints were ST6, ST7, SJ21, SJ17, SI18, Tai Yang, Yin Tang and LI4, confirming the effectiveness of this therapy, similar to Western therapies conventional, but of low cost and providing an improvement in the quality of life. They conclude that, as it has a low rate of side effects, its use can be continuous, being an excellent option for the control or treatment of pain in TMD patients.

Fernandes et al. (15), in a systematic review study from 2015, found 4 articles that met eligibility criteria and concluded that acupuncture was effective to alleviate the signs and symptoms of myofascial pain in patients with TMD, suggesting that it could be an alternative of treatment.

Jung et al. (16), identified 7 studies and found weak evidence of acupuncture as an alternative treatment for TMD symptoms, as the difficulty of finding an adequate sham group is an important limitation in these studies, among other limitations.

These review studies indicate that more high-quality studies are needed, with an adequate sample size, more homogeneous methods of diagnosis and application of acupuncture, long-term evaluation and most conclude that, within the results obtained, this indication of acupuncture can be done.

Our proposal to work with acupuncture in FOP/UNICAMP is to evaluate according to the energy syndrome presented by the patient and thus the objective of this study is to present the prevalence of these syndromes as well as the effectiveness of the proposed treatments. The hypothesis of this study was added: among the syndromes related to the occurrence of TMD, liver and heart alterations are the most prevalent and treatment with acupuncture will be effective for all syndromes. We present the following article in accordance with the TREND reporting checklist (available at https://lcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/lcm-21-60/rc).

Methods

Trial design

This is a non-randomized, retrospective longitudinal follow-up clinical study, reporting the experience of clinical care. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics committee (CEP FOP/UNICAMP No. 099/2008) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Participants

Participants are patients with TMD without distinction of muscle and/or joint origin, whose data were collected from 2008 to 2018 during consultations at the Acupuncture Clinic of FOP/UNICAMP, and who were treated with acupuncture according to the syndrome presented, within the concepts of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Data from participants were collected from attendance sheets.

Eligibility criteria

The study included patients who sought the acupuncture clinic at FOP/UNICAMP with TMD problems (muscle and/or joint) or who had been referred by dentists in the city of Piracicaba or other areas/departments of the faculty.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study included all those who required exclusive acupuncture treatment and whose care protocol for the diagnosed syndrome was used throughout the treatment. So, the inclusion criteria were patients with orofacial pain regardless of whether it is muscle or joint and exclusion criteria patients undergoing another type of treatment for orofacial pain and patients who did not complete 3 sessions.

Interventions

Exclusive individualized protocols for acupuncture care were construct at FOP\Unicamp. The answers of the anamnesis, and the clinical evaluation of the tongue and pulse were analyzed in order to formulate those protocols. In acupuncture, an energy assessment of the patient as a whole is performed. Face color conditions, the way you walk, voice tone, clinical and energetic conditions such as color, shape and texture of the tongue and pulse assessment are evaluated. After collecting and tabulating these data, the energy changes commonly found were observed and based on this, these protocols were elaborated. And during the anamnesis, the care protocol that was closest to the energy change presented by the patient was selected.

For each syndrome there was a set of acupoints as a treatment protocol described below:

- Syndrome 1: Qi and Xue stasis: SP10, Lu9, LV2+ST5 and ST6;

- Syndrome 2: Deficiency of Jing and Tin Ye (Spleen): K3, LI4, RM12 + SP12, SJ3, SJ21;

- Syndrome 3: Change in Emotional Balance (Changed Shen): H7, PC6, SI3, GB20 + SJ23;

- Syndrome 4: external wind with cold, humidity-heat: GB20, GB43 + SJ17, SI19;

- Syndrome 5: Spleen Yang Deficiency: RM12, SJ3, LI4, SP4 + DU15;

- Syndrome 6: Ascending Yang of Liver with internal wind: K7, LV2, GB34 + SJ17, GB20, GB39;

- Syndrome 7: Kidney Yin Deficiency with Chong Mai alteration: RM3, K7, K3, DU4, DU14 + local ashi points 0.25 mm × 30 mm needles were used, manufactured by Dongbang Medical Co., Ltd., Korea.

Needling was unilateral with a range of 5 to 10 needles. The patients were seen by extension course students, who are trained dentists and supervised by experienced acupuncturists (at least 5 years of experience), who checked all needle insertions and location, depth and DeQi attainment. The depth of needling was related to the size of the patient as well as obtaining the DeQi, felt by the acupuncturist as “needle hooked by the point”. The stimulation was manual and the needles remained for 20 minutes. The plan was for the patient to have a minimum of 3 sessions and a maximum of 12 sessions with a 1-week interval for each session. Patients were treated only with needling and each one following its own protocol, without adding any other method, such as moxa, suction cup or guasha. Patients were instructed to come with comfortable clothes and at least 1 hour apart from the last meal, they were instructed not to come fasting and if they needed to drive, a companion was requested, because of the great relaxation they could feel after the acupuncture session.

Outcome

The dependent variable in this study was the assessment of pain using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), which ranged from 0 (no pain) to maximum pain, with initial assessment and at the end of treatment.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis in relative and absolute terms was used, this is, number of participants and distribution according Syndrome as well the effectiveness of the indicated protocols pointed as percentage of success in decrease pain. The difference between initial and final Vas was obtained by the Student’s t-test and to compare the effectiveness of the syndromes by the reduction rates of the VAS (VASi − VASf)/VASi ×100. We use IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.

Results

There were 50 volunteers (41 women) who met the inclusion criteria in 10 years of offering an acupuncture extension course, from 2008 to 2018. There was a variation in the number of sessions from 3 to 12 sessions, the most frequent being 4 sessions (24% of volunteers). Of those who answered the question about previous experience with acupuncture (n=31), practically half had never had acupuncture (n=15).

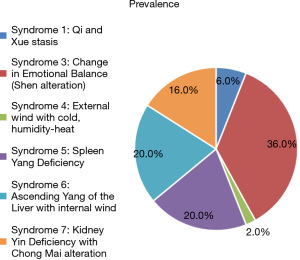

The most prevalent Syndrome was emotional imbalance, that is, altered Shen with 36% of occurrence (n=18), followed by Spleen Yang deficiency syndrome and Ascending Liver Yang, equally with 20% of occurrence (n=10 in each group). The Kidney Yin Deficiency Syndrome with Chong Mai alteration was 16% (n=8), with only 1 case of External Wind with Cold, Humidity-heat and 3 cases of Qi and Xue stasis, generating a percentage of occurrence of 6%.

There were no cases of Jing and Tin Ye (Spleen) deficiency, as shown in Figure 1.

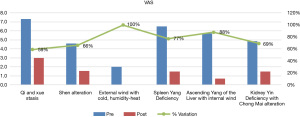

There was a 74% reduction in VAS in the group as a whole, with the initial mean VAS being 5.36 with sd =3.37 and the final VAS being 1.42 with sd =2.05, with a statistically significant decrease in pain P<0.001.

The variation in pain reduction was 59% to 100%, with the greatest reductions being for the syndromes External Wind with Cold, Humidity-heat (100%) and ascending Yang of the Liver with internal wind (88%), according to Table 1 and Figure 2.

Table 1

| Syndrome | VAS initial | VAS final | VAS reduction rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syndrome 1: Qi and Xue stasis | 7.33 | 3.00 | 59% |

| Syndrome 3: Change in Emotional Balance | 4.61 | 1.56 | 66% |

| Syndrome 4: External wind with cold, humidity-heat | 2.00 | 0.00 | 100% |

| Syndrome 5: Spleen Yang Deficiency | 6.50 | 1.50 | 77% |

| Syndrome 6: Ascending Yang of the Liver with internal wind | 5.70 | 0.70 | 88% |

| Syndrome 7: Kidney Yin Deficiency with Chong Mai alteration | 4.88 | 1.50 | 69% |

| Total | 5.36 | 1.42 | 74% |

VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Discussion

Shen alteration was the most prevalent syndrome (36%), followed by the occurrences of ascension Liver Yang syndrome (20%) and Spleen Yang deficiency (20%) in this study, which despite not having been designed to have external representation, it may be indicating a profile that is likely to occur in population groups, as it is reported in the literature that psychological changes are very common risk factors for TMD (18), including compromising quality of life (19). TMD symptoms often become chronic and, being associated with psychological factors, they can compromise daily sleep, social activities at school or work, affective and cognitive balance, and physical activities (20).

Thus, the search for new therapeutic approaches is relevant for this muscle-skeletal change in the face, which leads to suffering and with a high prevalence, especially when in a subgroup of patients with TMD, no treatment is effective (21), these “non-responders” have higher depression, pessimism and catastrophizing scores and lower self-efficacy and coping scores than their peers (22).

This therapeutic approach to TMD with acupuncture, diagnosed with syndrome in the present study, was effective as it reduced painful symptoms by 74%, and becomes even more advantageous as it is a non-invasive (non-surgical) therapy that seeks to balance the organism when diagnosing the associated syndrome.

When the needle is inserted into acupuncture points, nociceptive stimuli are promoted that release neurotransmitters such as bradykinin, histamine, substance P and prostaglandin. Subsequently, they are transported to the central nervous system by fibers. Delta and fiber C in the hypothalamic pathways producing β endorphins, cortisol, and serotonin, via the midbrain pathway activating the interneurons that trigger the release of serotonin and norepinephrine and the spinal level with the release of dynorphins, enkephalins which are opioid substances that modulate the biochemical process of pain (23).

It is known that TMD symptoms must be treated promptly, as chronic pain becomes more difficult to control due to psychological deterioration and somatization (24). Factors of psychological distress, poor sleep and genetic polymorphisms related to generalized changes in pain processing are more commonly associated with the development and persistence of TMD than mechanical factors and therefore, these factors have been the focus of current research (21).

Some studies in the literature still point out the traumatic factor being important, as in the clinical findings of the OPPERA case-control study regarding the history of trauma, parafunction, other pain disorders, health status and other clinical examination data of the masticatory system (25). These factors can cause Qi and Xue stasis and this Qi and Xue stasis syndrome was the one that brought patients with higher initial pain, confirming the information that stopped energy and blood cause pain, including in the TMJ region. Acupuncture treatment achieved a 59% reduction in initial pain. Thus, in some cases it becomes necessary to integrate other treatments.

By balancing the Shen of these patients, the result was a 66% reduction in pain, reinforcing the role of emotions in this multifactorial TMD, as reported in the literature in the cohort study that depressive and anxiety symptoms should be considered risk factors for pain in TMD (18,26). These findings provide evidence that measures of psychological functioning can predict the onset of TMD (18), and maintenance of TMD with a significant relationship between painful TMD, depression and anxiety (27), reinforcing the importance of seeking tools that identify and seek balance for this strong associated factor. Patient assessment often fails to recognize that sensory and emotional dimensions are fundamental aspects of pain and authors such as Sharma et al. (28) emphasize the importance of adopting this biopsychosocial model when approaching patients with TMD, which leads us to the approach that TCM indicates when evaluating the patient holistically.

Thus, TMD has a multifactorial etiology, including physical, genetic, and psychosocial factors. Longitudinal studies addressing the onset and persistence of TMD pain confirm that they are determined by the person’s lasting characteristics, as well as by the mutual interaction with variables in temporal evolution (20,29,30). This syndromic diagnosis by TCM comes to contribute as an important path, since, being the multifactorial TMD, the identification of factors becomes a challenge and this syndromic approach shows us to be a possible path, with promising results.

Due to this multifactorial nature, treatment usually consists of a series of methods (31) such as training, self-care and abandoning harmful habits, physical therapy such as ultrasound and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), laser therapy (32,33), intraoral devices (34), medications (35), behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, Botox injection (36) and PRP (34), acupressure and therapeutic massage (37), as examples.

Okeson et al. (38) point out that TMD-related pain is a major clinical challenge in dentistry and represents one of the main causes of non-dental pain in the orofacial region and thus non- invasive treatments such as laser therapy have been proposed (39), in which the combination of low-intensity laser and TENS caused accelerated pain recovery and resolved movement restrictions, but the authors do not describe which areas/points were used for such applications, probably without this approach due to the syndrome. Even within the protocols that apparently the emotional state would not be involved, such as external wind with cold, it is known that one of the ways of external factors to overcome the true energy would be if it is not adequate and one of the ways of greater wear of this energy is the emotions, because a wear of the Shen leads to an energy deficit greater than physical wear.

The energy deficiency, found in the Spleen and Kidney Yin Deficiency syndromes, may also have been consequences of emotional factors and so it is proposed that treating Shen in TMD alterations will be almost protocol. Since TMD exhibits many clinical features similar to other musculoskeletal pain conditions and TMD represents a group of orofacial pain symptoms that share similarities with other chronic pain conditions, this approach can be extrapolated to other conditions.

The aspects of Spleen Yang deficiency and ascending Yang of the Liver can also be explained by major emotional strains related to anger/frustration in the increasingly competitive world, which were situations routinely identified in the anamnesis of many of these patients. With the interference of dominance of an exacerbated Liver it would lead to the consumption of energy from the Spleen. This spleen energy could also be weakened by its own harmful habits of poor eating and/or ruminant thoughts.

In the Liver Yang Ascension Syndrome, in addition to being associated with the emotional stress of this ascent, there is the participation of muscles and tendons that make up this joint. There are invasive agentes that include ischemic compression, passive stretching, nerve stimulation by transcutaneous electrostimulation, massage, biofeedback, ultrasound, infrared laser, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (40).

In a recent systematic review, Vier et al. (41) verified the effectiveness of a minimally invasive technique called dry needling, which involves the application of sterile monofilament needles that penetrate the skin and muscles, stimulating points underlying the trigger point region to regulate neuromuscular pain and movement deficits. It is noteworthy here that the treatments performed in this study did not aim at deactivating the trigger point, but rather on the circulation of Qi and Xue, in addition to the characteristics of each acupoint, leading to balance within each syndrome.

In times of pandemic, the study by Asquini et al. (42) demonstrated that people with chronic TMD were more susceptible to COVID-19 stress with deterioration of the psychological state, worsening of central sensitization characteristics and increased intensity of chronic facial pain, the role of stress being a possible amplifier of central sensitization, anxiety, depression, chronic pain, and pain-related disability in people with TMD. The outbreak of COVID-19 can lead to major impacts on oral conditions and the psychological factors associated with the pandemic can lead to an increased risk of developing, worsening and perpetuating TMD. Orofacial pain specialists should be aware of this fact and integrative practices can contribute to this approach. The demonstrated success of minimally invasive options may indicate that they may be approaches considered as the initial option for cases refractory to conservative (non-invasive) approaches, compared to open joint surgery, which is rare nowadays and reserved for specific situations (12). In our study, acupuncture points as a promising therapy, especially when the syndrome is identified. Syrop (43) indicates that TMD is successfully managed by one or another of the current modalities, once correct diagnosis and proper management are used. Hence the importance and contribution of an integrative medicine, in which concepts are added together and in this expanded approach, patients have their care with greater options for managing their pain.

Thus, special efforts must be made to avoid the early use of invasive and irreversible treatments, such as occlusal therapy or surgery. Conservative (that is, reversible) and non-invasive treatment, such as education, self-care instructions, behavioral modification, physical therapies, medications and interocclusal devices, are endorsed for the initial care of almost all TMD and acupuncture is included in this recommendation in view of the results of this therapy in the literature and in the present study.

Systematic reviews dealing with the theme TMD and acupuncture (13-16) indicate that there are favorable results of this therapy in the approach of patients with TMD, especially those of muscular origin, however, point to some items that are necessary to be studied, among them the best combination of points. In this aspect, this article introduces a novelty in the approach of patients with TMD, which is the syndromic diagnosis, which is essential when treating with acupuncture.

It is interesting to note that the prevalence of syndromes was associated with a multifactorial etiology in which the emotional factor played a large part, considering that one of the most associated etiologies in the Western context is stress. Therefore, the results presented are promising, however it is emphasized that not all patients reached the absence of pain and that the maintenance of these results is not prospectively known. Another limitation of the present study was the lack of information on the origin of TMD pain (whether muscular, joint, or mixed), it is known that the effectiveness of acupuncture is greater for muscular TMD (44,45). However, even without this data, the results were positive, in a sample that probably included patients with joint or mixed pain. Another point to be considered is that the resolution of pain associated with TMD generates, as a consequence, the resolution of other associated symptoms, such as tinnitus, sleep disorders, dental apartment, among others, which were not measured in this study.

We emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing this dysfunction that affects one of the most complex joints in the human body. On the other hand, the acupuncturist can be of great help in helping with this pain management in patients with TMD, especially when reaching a specific diagnosis of the energetic alteration to which this “TMD symptom” is associated.

Conclusions

Shen alteration was the most prevalent syndrome and acupuncture therapy proved to be effective, with significant reduction percentages for all syndromic diagnoses presented and thus can be considered as one of the therapies for the management of TMD. In this retrospective study, the analysis showed the possibility of energy standardization and protocols for the acupuncture treatment of TMD.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TREND reporting checklist. Available at https://lcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/lcm-21-60/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://lcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/lcm-21-60/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://lcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/lcm-21-60/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics committee (CEP FOP/UNICAMP No.: 099/2008) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Yamamura Y, Yamamura ES. Propedêutica Energética da Língua e Pulsologia Chinesa. Center AO. Sao Paulo, 2009.

- International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP). Cephalalgia 2020;40:129-221.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014;28:6-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeResche L. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 1997;8:291-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Schwap M, Bristela M, Kundi M, et al. Sex-specific differences in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 2013;27:42-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Resende CM, Alves AC, Coelho LT, et al. Quality of life and general health in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Braz Oral Res 2013;27:116-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pigozzi LB, Pereira DD, Pattussi MP, et al. Quality of life in young and middle age adult temporomandibular disorders patients and asymptomatic subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021;19:83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dworkin SF. Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain-related disability found related to depression, nonspecific physical symptoms, and pain duration at 3 international sites. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2011;11:143-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (2018) Prevalence of TMJD and its signs and symptoms. Available online: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/facial-pain/prevalence. Accessed 18 June 2021

- Valesan LF, Da-Cas CD, Réus JC, et al. Prevalence of temporomandibular joint disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2021;25:441-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves DA, Dal Fabbro AL, Campos JA, et al. Symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in the population: an epidemiological study. J Orofac Pain 2010;24:270-8. [PubMed]

- Li DTS, Leung YY. Temporomandibular Disorders: Current Concepts and Controversies in Diagnosis and Management. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:459. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- La Touche R, Angulo-Díaz-Parreño S, de-la-Hoz JL, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders of muscular origin: a systematic review of the last decade. J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:107-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garbelotti TO, Turci AM, Serigato JMVA, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for temporomandibular disorders and associated symptoms. Rev Dor. São Paulo 2016;17:223-7.

- Fernandes AC, Duarte Moura DM, Da Silva LGD, et al. Acupuncture in Temporomandibular Disorder Myofascial Pain Treatment: A Systematic Review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2017;31:225-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung A, Shin BC, Lee MS, et al. Acupuncture for treating temporomandibular joint disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, sham-controlled trials. J Dent 2011;39:341-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dalewski B, Kamińska A, Szydłowski M, et al. Comparison of Early Effectiveness of Three Different Intervention Methods in Patients with Chronic Orofacial Pain: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Res Manag 2019;2019:7954291. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD, et al. Psychological factors associated with development of TMD: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain 2013;14:T75-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Resende CMBM, Rocha LGDDS, Paiva RP, et al. Relationship between anxiety, quality of life, and sociodemographic characteristics and temporomandibular disorder. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2020;129:125-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chisnoiu AM, Picos AM, Popa S, et al. Factors involved in the etiology of temporomandibular disorders - a literature review. Clujul Med 2015;88:473-8. [PubMed]

- Maísa Soares G, Rizzatti-Barbosa CM. Chronicity factors of temporomandibular disorders: a critical review of the literature. Braz Oral Res 2015;29:S1806-83242015000100300. [PubMed]

- Litt MD, Porto FB. Determinants of pain treatment response and nonresponse: identification of TMD patient subgroups. J Pain 2013;14:1502-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silvério-LopesS- Acupuncture-Concepts and Physiology, 2011 –cap 5. Electroacupuncture and Stimulatory Frequencies for Analgesia. Instituto Brasileiro de Therapias e Ensino (IBRATE) Curitiba Brasil. Available online: www.intechopen.com

- Ismail F, Eisenburger M, Lange K, et al. Identification of psychological comorbidity in TMD-patients. Cranio 2016;34:182-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohrbach R, Fillingim RB, Mulkey F, et al. Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain 2011;12:T27-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kindler S, Samietz S, Houshmand M, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms as risk factors for temporomandibular joint pain: a prospective cohort study in the general population. J Pain 2012;13:1188-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De La Torre Canales G, Câmara-Souza MB, Muñoz Lora VRM, et al. Prevalence of psychosocial impairment in temporomandibular disorder patients: A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 2018;45:881-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma S, Breckons M, Brönnimann Lambelet B, et al. Challenges in the clinical implementation of a biopsychosocial model for assessment and management of orofacial pain. J Oral Rehabil 2020;47:87-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohrbach R, Slade GD, Bair E, et al. Premorbid and concurrent predictors of TMD onset and persistence. Eur J Pain 2020;24:145-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conti PC, Bonjardim LR. Temporomandibular disorder, facial pain and the need for high level information. J Appl Oral Sci 2014;22:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dutra LC, Seabra EJG, Dutra GRSF, et al. Treatment methods of temporomandibular dysfunction: systematic review. Rev Aten Saúde São Caetano do Sul 2016;14:85-95.

- Souza ACOC, PereiraPC, Junior JDC. A influência da laserterapia de baixa Potência e do Ultrassom terapêutico na abertura da boca em pacientes com disfunção temporomandibular. Available online: https://acervomais.com.br/index.php/artigos/article/view/6006

- Ren H, Liu J, Liu Y, et al. Comparative effectiveness of low-level laser therapy with different wavelengths and transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain caused by temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil 2022;49:138-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Moraissi EA, Alradom J, Aladashi O, et al. Needling therapies in the management of myofascial pain of the masticatory muscles: A network meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. J Oral Rehabil 2020;47:910-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mujakperuo HR, Watson M, Morrison R, et al. Pharmacological interventions for pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;CD004715. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- da Silva GC, Lourenço AMS, Souza CT, et al. Use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of temporomandibular disorders: integrative review. Research, Society and Development 2020. DOI:

10.33448/rsd-v9i9.7491 . Available online: https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/749110.33448/rsd-v9i9.7491 - de Melo LA, Bezerra de Medeiros AK, Campos MFTP, et al. Manual Therapy in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain Related to Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2020;34:141-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okeson JP, de Leeuw R. Differential diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders and other orofacial pain disorders. Dent Clin North Am 2011;55:105-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mansourian A, Pourshahidi S, Sadrzadeh-Afshar MS, et al. A Comparative Study of Low-Level Laser Therapy and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation as an Adjunct to Pharmaceutical Therapy for Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Front Dent 2019;16:256-64. [PubMed]

- Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM. Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res 2014;7:99-115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vier C, Almeida MB, Neves ML, et al. The effectiveness of dry needling for patients with orofacial pain associated with temporomandibular dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Phys Ther 2019;23:3-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asquini G, Bianchi AE, Borromeo G, et al. The impact of Covid-19-related distress on general health, oral behaviour, psychosocial features, disability and pain intensity in a cohort of Italian patients with temporomandibular disorders. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245999. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Syrop SB. Initial management of temporomandibular disorders. Dent Today 2002;21:52-7. [PubMed]

- Shedden Mora MC, Weber D, Neff A, et al. Biofeedback-based cognitive-behavioral treatment compared with occlusal splint for temporomandibular disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2013;29:1057-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gil MLB, Zotelli VLR, Sousa MLR. Acupuncture as an alternative in the treatment of temporomandibular dysfunction. Rev Int Acupuntura 2017;11:12e5.

Cite this article as: Sousa MLR, Gil MLB, Montebelo MIL. Temporomandibular dysfunction: energy patterns for acupuncture treatment. Longhua Chin Med 2022;5:13.