The regulation of Chinese Medicine in the U.S.

Introduction

The United States of America is considered the third or fourth largest country in the world and the third most populated country with an estimated population of over 328 million according to the 2019 Census (1). While it is considered a racially diverse nation, it is also riddled with a history of interracial issues and centuries of immigration. As for politics, its 50 states have sovereignty to a great extent, but must also maintain a relationship with the federal government. Its cultural, racial diversity, and geographical size enables a development and maintenance of distinct historical, social, and political characteristics of each state. There is no universal health coverage for its citizens, and the issue of uninsured and underinsured citizens has continued to pose a serious threat to the overall health of the nation.

It is in this context that its citizens often turn to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), which include acupuncture and related treatment modalities as a viable option for healthcare. The 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (2), the most recent data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), states that about 33% of adults and 12% of children (age, 4–17) use complementary health approaches. Acupuncture ranks as the 11th most commonly used approach within the spectrum of complementary health approaches (3).

At a federal and national level, standardization of this ancient practice is only in its incipient stages in the U.S., fueled by the diversity between states, personalities, and organizations. The profession of acupuncturists itself only officially became an occupation in 2018 with the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Furthermore, that the profession has yet to achieve a unified whole is nowhere so evident as in the case of what to call this medicine in the U.S. The definition and the naming of this medicine, for example, remain very much controversial at this point. To illustrate, while acupuncture and its related modalities have originated from the present-day geographical areas of China, they have taken on a different personality in the U.S., where treatment systems from China, Korea, Japan, South East Asia, India, and the Worsley Five Acupuncture have existed together in harmony as training and practice modalities. Some of the popular options for the naming of this medicine include the inappropriate and outdated “Oriental Medicine” (OM) (4,5) and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Other options include Chinese Medicine (CM), Classical Chinese Medicine (CCM), Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (AOM), Traditional East Asian Medicine (TEAM), Acupuncture and East Asian Medicine (5,6), Acupuncture and Integrative Medicine, American Chinese Medicine, Traditional Asian Medicine (TAM) and so forth. There have been conscious attempts by different educational and professional organizations to disengage from using the word “oriental”, but the process of establishing a common name, however, seems to have just begun. It may take some time for the profession to abandon the use of OM and adopt a term that is both acceptable and appropriate by all stakeholders. The tumultuous historical and socio-political events that took place in Asia in the last century or so should also provide perspective to all constituents as well.

For these reasons, the term “Acupuncture and Traditional Medicine” (AcuTM) was adopted in this article to describe the study and the practice of medicine in the U.S. “Traditional Medicine” (TM), is also the official term that the World Health Organization adopted to describe medicine from different cultures (7).

Historically salient events concerning the development of AcuTM in the U.S. are intermingled in the training, regulation, and the practice of AcuTM. The origin of the practice of acupuncture in the U.S. may go back as far as the 1800s or with acupuncture treatment activities by early Chinese immigrants (5,8,9), but the singular even that defined the beginning of the acupuncture profession in the mainstream may be The New York Times article, published in 1971, detailing the acupuncture treatment the columnist and journalist, James Reston, received in China (10).

Since this publication, in the 1970s, organizations and training centers began to be established (11), largely located in the west and the east coast of the U.S. with a larger Asian population. Acupuncture licensing organizations and educational institutions also began to be established. In 1973, the State of Nevada became the first state to regulate and license the practice of acupuncture (12). Other states, such as California and Hawaii, soon followed. Education institutions also began springing up in the more populous areas to meet public demands. In 1975, the New England School of Acupuncture in Newton, Massachusetts (NESA), currently a part of Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, was established as the first acupuncture training institute in the U.S. On the west coast, Samra University of Oriental Medicine (SAMRA, closed since 2010) began operations in 1979 in California.

As the practice of acupuncture was becoming popular, stringent regulatory laws were passed to regulate AcuTM during this time as well. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for example, initially classified acupuncture needles as “investigational devices” in 1972, and then reclassified acupuncture needles in 1996 as Class II medical devices to be used safely by licensed practitioners (13).

In the 1980s, foundational professional organizations, such as the American Association of Oriental Medicine (AAOM, now American Association of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine, AAAOM), the first national organization for practitioners; and the Council of Colleges of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (CCAOM), an organization that promotes educational standards, were established in an effort to form a united front and to improve the standards of the profession (14). These two organizations co-founded the Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (ACAOM) in 1982 (11), which received recognition from the U.S. Department of Education (USDE) in 1988 to accredit master’s degree programs. The National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM), a national exam and certification agency, was also formed in 1982.

The 1990s saw active research in acupuncture when the National Institute of Health (NIH) established the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) in 1992. OAM greatly promoted the research and regulation of alternative medicine. The 1990s also saw active participation by physicians and other healthcare practitioners as acupuncture practitioners, which, due to the limitation of space, will remain a topic for future discussion.

The consistent theme that emerged concerning AcuTM in the U.S. is transformation and change as a result of complex historical and regulatory issues at the state as well as the federal level. This article will explore these transformations at significant junctures in the study, the practice, and the acceptance of acupuncture and traditional (AcuTM) medicine in the U.S.

Regulation and realities of studies in AcuTM

The study of AcuTM in the U.S. is regulated at different levels depending on the target audience and the goals of training. The immediate goal for most students studying AcuTM is to obtain acupuncture licensure appropriate for the location of practice. Forty-seven states and the District of Columbia currently have acupuncture practice laws in place. Alabama, Oklahoma and South Dakota do not have acupuncture practice law (15,16). In general, AcuTM training programs have to be approved by the individual state’s acupuncture licensing board and the state’s educational department. The program also has to obtain accreditation status with ACAOM. Currently, ACAOM is the only accreditation agency recognized by the USDE to either accredit or pre-accredit AcuTM programs (17). The institution must also work with NCCAOM to ensure their students are able to sit for licensing exams as necessary and appropriate for each state. Typically, institutions in eastern and western coasts with a longer history of acupuncture and larger populations have more extensive requirements compared to mid-American states. California, for example, exceeds ACAOM’s program requirement for a Master’s Level Professional Acupuncture Program with Chinese Herbal Medicine Specialization by about 900 hours (18).

An applicant must also pass licensing exams as specified by each state’s licensing board. Licensing exams consist of a combination of one or more of the following three categories:

- One or more of NCCAOM exam modules: Foundations of Oriental Medicine, Acupuncture with Point Location, Chinese Herbology, and Biomedicine. These modules are offered in English, Chinese, and Korean.

- NCCAOM certification: Diplomate of Acupuncture (Dipl. AC), Diplomate of Chinese Herbology (Dipl. CH), Diplomate of Oriental Medicine (Dipl. OM).

- State specific licensing exam.

NCCAOM is a national acupuncture certification organization, and one or more of its modules or a certification are required in most states with acupuncture practice acts in place (15). States such as Nevada require the NCCAOM Dipl. OM Certification, while Washington requires all NCCAOM modules except for the Chinese herbology. NCCAOM certification, however, is not required in Washington. Some states, such as Maine, specify that the NCCAOM examination must be taken in English, since NCCAOM modules are offered in Chinese and Korean as well. In still another case, Texas specifies that applicants have three attempts to pass each NCCAOM module.

States such as Nevada, New Jersey, and California administer state specific exams, which are mostly state jurisprudence exams. These state specific exams are administered once the applicant has successfully passed the required NCCAOM exams. In Nevada, Dip. OM certification is required, which means passing all four modules, and then applying to obtain the appropriate certification. In New Jersey, the applicant must pass all four NCCAOM modules, but a certification is not required. California is an exception. It administers the state specific California Acupuncture Licensing Examination (CALE) as the only licensing exam. Passing NCCAOM exams or certification is not required in California.

States may also have state-specific, unique, requirements for licensure. New Jersey, for example, requires applicants to hold a bachelor’s degree (19), which is not a standard requirement for other licensing boards since the standard admissions requirement to enter an AcuTM program is 2 years of college. These state specific regulatory requirements certainly pose a challenging reality for all the stakeholders. The state requirements themselves are also constantly changing and transforming. These challenges represent the historical, social, and political issues that each state may have experienced in the development and the establishment of AcuTM.

The realities of studying AcuTM

The reality for many AcuTM training programs, as well as its students, are changing, and possibly not for the better. As of January 2018, there were 62 accredited AcuTM institutions (16). The number of AcuTM training programs has also decreased in California from 23 to 15 (16). During this time, some of the institutions have merged with regionally accredited universities, such as NESA merging with Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.

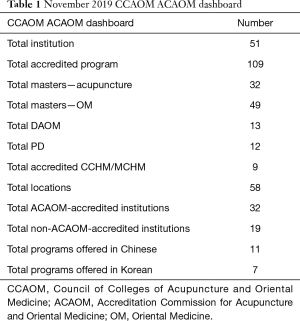

ACAOM released the following unpublished figures in November 2019 in Table 1 for a CCAOM meeting.

Full table

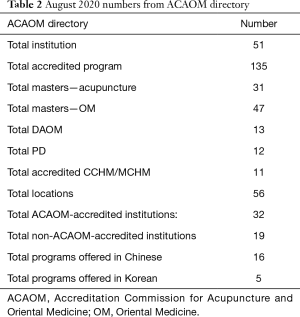

An examination of ACAOM’s “Directory of ACAOM accredited and pre-accredited programs/institutions” shows the following numbers as of August 2020 (20): Table 2.

Full table

When these numbers are compared to the 2018 numbers, the number of accredited institutions decreased in the last 2 years [2018–2020] from 62 to 51. While the number of accredited programs may have increased, this may be due to the increase in Chinese Herbal certification. Between 2019 and 2020, except for the total accredited programs, the numbers have either remained the same or have decreased slightly. Between 2018 and 2019, seven ACAOM affiliated institutions or branches have closed. The number of training programs in California has also decreased further to thirteen between 2018 and 2020. Institutions on the west and east coasts still comprise a majority with six located in Florida, four in New York.

Student enrollment in ACAOM programs also seems to be decreasing according to ACAOM’s program enrollment information available online. The total enrollment for 2010 was 7,867. In 2015, it was 7,771. In 2018, the number decreased further to 6,788 (21). These enrollment numbers may be decreasing further with the present COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. severely impacting the entire education system financially and academically. There may be additional institutions that close as a result of financial difficulties arising from the pandemic.

Things have not been easier for the students either. Students still have to consider the financial cost of education, including the cost of examination and licensure, as well as living expenses during these uncertain times. National statistics regarding the percentage of students becoming successful practitioners are lacking. There is also the reality of receiving practical clinical education via online platforms. Along with much of the rest of the country, the usual onsite, practical-skills focused acupuncture clinics have also had to move online. Nearly 100% of education is now being done online, as is evident in various notifications posted on institutional websites. But how do you obtain practical clinical skills online? Because of these reasons, some students have decided to delay enrollment or search for more lucrative areas of study. What will happen to the AcuTM training post-COVID remains ever uncertain.

Regulation and reality of the professional practice of AcuTM

There are no national standards for the practice of acupuncture in the 49 states and the District of Columbia with acupuncture practice act. At the foundational level, ACAOM’s programmatic requirements for the Master’s in Acupuncture may serve as the basis, but those requirements have also changed over a time, and there are practitioners that were licensed prior to states requiring ACAOM accreditation or NCCAOM certification. As such, the level of training and background vary widely between practitioners and between states.

Recognition of acupuncturists as a profession at the national level was slow to come. In 2018, the BLS finally recognized acupuncturists as an occupation, and has included acupuncturists in its final 2018 BLS Occupational Handbook with the new Standard Occupational Classification code for Acupuncturists (22). Acupuncturists, however, were placed under the category of 29-1290 “Miscellaneous Healthcare Diagnosing or Treating Practitioners”, in the same group as dental hygienists, homeopathic doctors, and naturopathic physicians; which clearly indicates that BLS did not see the practitioners in this group as distinct or significant enough to be given separate designations.

A more recent landmark decision concerning acupuncture was made in January 2020 when the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced its historic decision to cover acupuncture for low back pain. An examination of the ruling, however, shows that acupuncturists have been defined as auxiliary personnel according to this decision, and “must be under the appropriate level of supervision of a physician, physician assistant, or nurse” (22). There are states, such as California, where licensed acupuncturists are considered primary healthcare givers, but in order to apply for these services, acupuncturists have to be supervised.

Depending on the strength of the licensing board, there are major differences in the scope of practice and the licensure title. The two obvious areas of differences in the scope of practice are on herbal prescription and injection therapy. New Mexico and Texas require herbal exams, and herbs are within the scope of practice (23). The issue of herbal inclusion is further complicated by whether the licensing board requires the NCCAOM Chinese Herbology module. States such as Washington, Oregon, and New York include Chinese herbs in the scope of practice, but do not require the NCCAOM Chinese Herbology module (23).

Injection Therapy is another area of major difference between states. It is allowed in some of the states, such as Colorado, Florida, Nevada, New Mexico, and Washington; but is not allowed in other states. Regulations or usage vary widely regarding injection therapy even between the states that allow injection therapy. States such as Colorado and Florida have AcuTM practitioners that actively use injection therapy. Nevada, on the other hand, appears to be only in the beginning stages of using injection therapy.

Most of the states that allow injection therapy often have different acupuncture license titles. For example, in Florida, the practitioner title is Acupuncture Physician. For Nevada and New Mexico, the licensure title is Doctor of Oriental Medicine (OMD or DOM). In Washington, the official practitioner title is Acupuncture and East Asian Medicine Practitioner (AEMP) (24). The designation of doctor in the licensing title does not indicate that the practitioner has graduated from a doctoral program. These titles are the designation for the license, and do not represent the practitioner’s educational attainment.

The predominant licensing title is L.Ac, with 43 states either opting to use the title of L.Ac., or a variation of L.Ac, such as Acupuncturist (District of Columbia), Registered Acupuncturists (Michigan), and so forth. These different licensing titles reinforces the uniqueness of each state, and also represent the relationship acupuncture may have had with other healthcare professions within the state, which may have either supported or challenged the profession of acupuncture in that state.

Realities of practice

The BLS published the estimated national median wage for “acupuncturists and healthcare diagnosing or treating practitioners, all other” as $42.82/hour and $89,060/annual as of May 2019 (25). This wage information includes other healthcare diagnosing and or treating practitioners such as dental hygienists, homeopathic doctors as well as naturopathic doctors as defined by BLS. There is no separate calculation for acupuncturists available from BLS. Occupations such as hygienists and naturopathic doctors, however, receive different training, and practice in different medical settings. There is no national prevailing wage information available for acupuncturists.

More realistic and accurate information may be gleaned from NCCAOM’s Job Analysis surveys from 2008, 2013, and 2017; and California’s 2015 Occupational Analysis. Since these surveys are based on personal responses, they may not represent an accurate portrayal of the profession. Nevertheless, since data at national level do not exist, these surveys will be correlated to studies done on acupuncturists as a profession, and used as main sources to derive basic quantitative and qualitative information regarding acupuncturists.

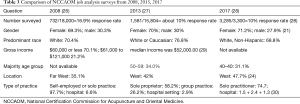

Table 3 was compiled by culling specific information from NCCAOM Job Analysis Survey of 2008, 2013, 2018. These three surveys, however, did not have the same questions.

Full table

Based on these numbers, the median income for acupuncturists appears to have increased from over 70% earning less than $60,000 to the occupation’s median earning of $52,000 in 2013. Another NCCAOM survey that compared data collected in 2014, 2015, 2016 of recertifying diplomates (n=1,047) showed that 70% of acupuncturists were female, with the average age of 52 years, earning about $40,000 and $60,000 per year (30).

Data culled from California Acupuncture Board’s 2015 Occupational Analysis paint a largely similar picture of a typical acupuncturist. Of the surveyed 8,000 Californian L.Acs, 11% [957] responded. The final sample size was 485. The majority were sole owners (59.8%). The median income (50%) fell in the $40,000–$59,000 income range (31).

In another study done in 2018, the total number of acupuncturists as of January 2018 in the U.S. was 37,886, with California having the most acupuncturists [12,135], representing 32.03% of total active licensed acupuncturists (16). Along with California, New York (11.71%) and Florida (7.13%) comprised more than 50% of the acupuncturist population. The study saw an increase of 257% since 1998. According to the study, the total acupuncturist density, or the number of acupuncturists per 100,000 in the U.S. was 11.63 with Hawaii having the highest density of 52.82 (16). Acupuncturists were more likely to practice in states with a larger Asian population and with a history of acupuncture regulation.

The portrait of a typical licensed acupuncturist that emerges from these studies, then, is that she is a white female, between the age of 40–49, who makes about $40,000–$60,000. She will be engaged in a solo private practice in an urban area, where there may be a large population of Asians.

While the data from the above study as well as occupational analysis surveys may show that the total number of acupuncturists is increasing, the number of newly licensed acupuncturists may actually be decreasing. The enrollment numbers for ACAOM programs have been decreasing steadily over the last 10 years. In addition, a compilation of the number of applicants sitting for CALE seems to have been decreasing over the last 10 years (32). In 2000, there were 1,137 total applicants, but only 980 in 2011. The number decreased further to 866 in 2017. Since CAB began using computerized testing from October 2018, a more recent quantitative compilation is not yet available. The current pandemic will probably decrease the number of applicants further, and it is unclear what may come in the practice of acupuncture.

Regulation and reality of Chinese (AcuTM) phytotherapy

In the U.S., AcuTM medicinal herbs are regulated by the FDA. The FDA passed the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) to classify herbs as dietary supplements, not subject to strict processes required for standard drugs (33). As a CAM product, AcuTM medicinal herbs fall within FDA’s Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act or Public Health Service Act (34). While the usage of herbs and supplements is included in the scope of practice for most of the 48 states and the District of Columbia, AcuTM medicinal herbs do not exist as a separate category in the practice of AcuTM in the U.S.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), about one in five Americans use herbal products (35). Research on herbal medicinals has been difficult and definitive conclusions have not been made by NCCIH. The “Herbs at a Glance” webpage of NCCIH simply lists some of the more popular herbs and information, such as potential side effects and caution as well as scientific information. Some of the herbs on this page that are relevant to the study of AcuTM herbs include Aloe Vera (lu hui), Asian Ginseng (ren shen), Ginkgo (bai guo), and so forth. Again, they are not used as medicines, but for general consumption (36).

Since AcuTM medicinal herbs are classified as dietary supplements, they are easily available for public consumption in grocery stores, health food stores. They are also available in a more professional setting from companies that specialize in Chinese herbal medicine. These companies sell their products specifically to licensed acupuncturists and practitioners as either online companies or offline stores. These medicinal herbs are available as raw herbs, pills, caplets, granules, liquids, extracts and so forth. They are available either as individual herb or as popular formulas in its original name or as interpretation of the formulas. For example, Xiao Yao San, a popular formula often prescribed by practitioners to relieve stress, may be available as Free & Easy Wanderer, and used to restore emotional balance. It is, however, common for most consumers of herbal products to self-diagnose and self-medicate (37).

In addition to the FDA, the U.S. is a member of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). CITES restrictions also affect the usage of Chinese medicinal herbs. Countries such as the UK, Canada, Australia, and Germany are also members of CITEs. A list of restricted and banned Chinese medicinal herbs have been compiled in the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) (38), and is the most comprehensive list to date (38).

Occasionally, the U.S. FDA may ban the sale of dietary supplements, as in the case of ephedrine alkaloids in 2004, which was originally marketed for weight loss (39). Supplements containing the ingredient caused high health risk, especially possible cardiovascular issues, and the herb was banned. Without going into all the details of challenges and confusion stemming from such regulatory actions, they often have a domino effect on the training and the practice of acupuncture and herbs in the U.S. Ephedra is the main ingredient in ma huang (Ephedra Sinensis), and it is an essential ingredient in many Chinese herbal formulas. As a result, ma huang as well as formulas that contain ma huang were removed from some of the licensing exams, such as the CALE (40,41). NCCAOM, however, included ma huang and medicinal formulas in their list of examination herbs and formulas (42). In addition, the herb ma huang and formulas that contain ma huang were also removed from herbs and formulas sold by Chinese herbal companies. Research on the usage of Chinese medicinal herbs in the U.S. remains largely unexplored, and additional research is necessary.

Level of acceptance by population

A generally accepted understanding regarding the level of acceptance of acupuncture in the U.S. is that there has been a gradual increase in the usage of acupuncture by Americans. The complementary health approaches sections of 2007 and 2012 NHIS contain useful information on this topic. NHISs are conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, and is a part of the CDC. More up-to-date information is not readily available, however.

According to the 2007 NHIS, about 6.7% (12.7 million) of the 27,692 adults sampled reported to have used acupuncture in their lifetime (43). During that time, about of adults and 12% of children have used some form of Complementary and Alternative Therapies, amounting to about $33.9 billion out-of-pocket expenses for CAM usage. In 2007, then, about a fifth (20%) of the adults using Complementary and Alternative Therapies have used acupuncture in their lifetime.

In another study published by CDC that analyzed trends in the usage of CAM between 2002–2012, the authors note that “there was a small but significant linear increase in the use of homeopathic treatment, acupuncture, and naturopathy” (3). This study combined data from 88,962 adults aged 18 and over for the 2002, 2007, and 2012 surveys for a detailed comparison. According to this study, the linear increase in Acupuncture was a small 0.4%. During this time period there was a 3.4% change for the usage in Yoga, Tai chi, and Qi gong, and 1.9 quadratic increase for massage (3). Acupuncture ranked as the 11th as a complementary health approach in 2012.

A common user of acupuncture was akin to a typical acupuncturist in 2012. The most common acupuncture user is:

- 41–65 years (47.4%);

- Female (69.6%);

- Non-Hispanic (85.3%) and/or white (78.1%);

- Usually in very good to excellent health (60.8%).

Increased usage and acceptance of acupuncture in the U.S. may be gleaned further by the coverage of acupuncture treatment by health insurance companies. States, such as Florida, Maine, Montana, Nevada, Texas, Virginia, and Washington State among others, mandate acupuncture coverage; and in California, acupuncture is considered an “essential health benefit” by Medi-Cal, California’s public health insurance program that provides medical services to Californians with limited income and resources (44).

An employer health benefits survey conducted in 2013 by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research Education Trust showed that 52% of plan members had coverage for acupuncture (45). Another indicator is a patient satisfaction survey that American Specialty Health (ASH) conducted in 2014 and 2015 of 89,000 managed network patients through a network of 6,000 U.S. acupuncturists (46). ASH is a company that manages plans for non-drug physical medicine services. Overall finding include:

- 93% indicated successful treatment of primary conditions by their provider;

- 99% rated their quality of care and service as good to excellent;

- 96.7% for national and 96.2% in California would recommend their acupuncturist to family and friends.

While one could argue that a company such as ASH must promote its providers, an unsuccessful and unsatisfactory treatment modality probably would not be considered a solid business venture by a company such as ASH.

Despite the popularity of acupuncture as a treatment modality in bicoastal areas such as New York and California, the available statistics on acupuncture shows that acupuncture is still in its beginning stages as a profession in the U.S., and also in terms of popular acceptance. Nevertheless, acupuncture, in particular, has been a popular pain management option with the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and VHA’s decision in 2018 to employee acupuncturists is widely known. The future landscape may look very different for acupuncture as one of the viable non-Opioid alternatives to pain management. For now, things are in flux, and the future of medicine will continue to transform and change.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Ramon Calduch Farnòs) for the series “Regulation of Chinese Medicine in the Different Countries of the World” published in Longhua Chinese Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/lcm-20-37). The series “Regulation of Chinese Medicine in the Different Countries of the World” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts United States. Washington DC: United States Census Bureau, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Statistics from the National Health Interview Survey: 2012 national health statistics. Bethesda: National Institute of Health. [Updated 2020 Aug 29; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/statistics-from-the-national-health-interview-survey

- Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Report 2015;1-16. [PubMed]

- Suh Y. A case for traditional Asian medicine. Acupuncture Today. 2020. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.acupuncturetoday.com/digital/index.php?i=743&a_id=33776&pn=27&r=t&Page=27

- Phan T. American Chinese medicine. PhD [dissertation]. London: University College London, 2017.

- Journal of the American Society of Acupuncturists. Author guidelines. 2019 [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.meridiansjaom.com/author-guidelines.html

- World Health Organization. Traditional, complementary and integrative medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.who.int/traditional-complementary-integrative-medicine/about/en/

- Cassedy JH. Early uses of acupuncture in the United States, with an addendum (1826) by Franklin Bache, M.D. Bull N Y Acad Med 1974;50:892-906. [PubMed]

- Lee, M. Insights of a senior acupuncturist. Boulder, CO: Blue Poppy Press; 1992.

- Reston J. Now, about my operation in Peking. The New York Times. 1971. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1971/07/26/archives/now-about-my-operation-in-peking-now-let-me-tell-you-about-my.html

- Stone JA. The status of acupuncture and oriental medicine in the United States. Chin J Integr Med 2014;20:243-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nevada Legislature. Memorializing Nevada’s first acupuncturist, Dr. Yee Kung Lok. Session/76th ACR 9. Carson City: Legislature Session. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.leg.state.nv.us/Session/76th2011/Bills/ACR/ACR9.pdf

- Food and Drug Administration. Reclassification of acupuncture needles for the practice of acupuncture. 61FR 64616-Medical Devices. White Oak: GAO (US); 1996. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-1996-12-06/96-31047/summary

- Council of Colleges of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (CCAOM). History. Baltimore: CCAOM. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.ccaom.org/ccaom/History.asp

- National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM). State licensure requirements interactive map. Washington DC: NCCAOM. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/state-licensure/

- Fan AY, Stumpf SH, Faggert Alemi S, et al. Distribution of licensed acupuncturists and educational institutions in the United States at the start of 2018. Complement Ther Med 2018;41:295-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (ACAOM). About us. Eden Prairie: ACAOM, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://acaom.org/about-us/

- In order to be an approved educational and training program in California, the institution has to offer a curriculum that is at least 3,000 hours (2,050 hours didactic, 950 supervised clinical instruction hours). Californian institutions maintain ACAOM’s current Master’s Level Professional Acupuncture Programs with Chinese Herbal Medicine Specialization, which requires a minimum of 146 semester credit (2,190 hours). ACAOM. ACAOM comprehensive standards and criteria standard 7: program of study. Eden Prairie: ACAOM, 2020. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://acaom.org/comp-standards-7/; and California Acupuncture Board (CAB). Laws and regulations relating to the practice of acupuncture: approved educational and training programs article 1. 4927.5. Sacramento: CAB, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.acupuncture.ca.gov/pubs_forms/laws_regs/laws_and_regs.pdf

- New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs. Acupuncture examining board frequently asked questions. Newark: Acupuncture Examining Board, 2017. [Updated 2019 Dec 4; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/acu/Pages/faq.aspx

- ACAOM. Directory of ACAOM accredited and pre-accredited programs/institutions. Eden Prairie: ACAOM, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://acaom.org/directory-menu/directory/pg/3/

- ACAOM. Enrollment in ACAOM accredited and pre-accredited programs. Eden Prairie: ACAOM, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://acaom.org/about-us/enrollment-in-acaom-accredited-and-pre-accredited-programs/

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Standard occupational classification manual. Washington DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor, 2018. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/soc/2018/soc_2018_manual.pdf

- NCCAOM. States that include Chinese herbs in the scope of practice for acupuncturists. Washington DC: NCCAOM, 2018. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/Chinese%20Herbs%20Regulation%20Map%2010-2019.pdf

- Washington State Legislature. Acupuncture and eastern medicine. Olympia: Washington State Legislature, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=18.06&full=true

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Occupational employment and wages, May 2019 Standard occupational classification manual. Washington DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor, 2019. [Updated 2020 July 6; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291298.htm

- Ward-Cook K, Hahn T. NCCAOM 2008 job task analysis: a report to the acupuncture and oriental medicine (aom) community. Washington DC: NCCAOM, 2010. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/JTA%202008%20Report.pdf

- Wang Z. Foundations of oriental medicine, biomedicine, acupuncture with point location, Chinese herbology job analysis report 2013. Washington DC: NCCAOM. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/NCCAOM_2013_JA_Report.pdf

- Ward-Cook K. NCCAOM 2017 job task analysis: a report to the profession of acupuncture and oriental medicine. Washington DC: NCCAOM, 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/2017%20NCCAOM%20Job%20Analysis%20Study%20Full%20Report%20with%20Appendices.pdf

- Ward-Cook K. Descriptive demographic and clinical practice profile of acupuncturists: an executive summary from the NCCAOM 2013 job analysis survey. Washington DC: NCCAOM. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/Executive_Summary_Descriptive_Demographic_and_Clinical_Practice_Profile_NCCAOM_2013_Job_Analysis.pdf

- Ward-Cook K, Reddy B, Mist S. A snapshot of the AOM profession in America: demographics, practice settings and income. Meridians J Acupunct Orient Med 2017;4:13-20.

- CAB. Occupational analysis of the acupuncturist profession. Sacramento: CAB, 2015. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.acupuncture.ca.gov/about_us/materials/2015_occanalysis.pdf

- CAB. Examination statistics. Sacramento: CAB, 2020. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.acupuncture.ca.gov/students/exam_statistics.shtml

- FDA. Dietary supplements. Whiteoak: FDA. [Updated 2019 Aug 17; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements

- FDA. Complementary and alternative medicine products and their regulation by the Food and Drug Administration: draft guidance for industry. Whiteoak: FDA, 2007. [Updated 2007 March 2; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/complementary-and-alternative-medicine-products-and-their-regulation-food-and-drug-administration

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). Traditional Chinese medicine: what you need to know. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health. [Updated 2019 April; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/traditional-chinese-medicine-what-you-need-to-know

- NCCIH. Herbs at a glance. Bethesda: National Institute of Health. [Updated 2020 Aug 30; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance

- Hui K, Yu J, Zylowska L. The progress of Chinese medicine in the United States. Los Angeles: UCLA, 2002. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://cewm.med.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2002HuiKProgressChineseMedInUS.pdf

- Fleischer T, Su YC, Lin SJ. How do government regulations influence the ability to practice Chinese herbal medicine in western countries. J Ethnopharmacol 2017;196:104-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NCCIH. Ephedra. Bethesda: National Institute of Health. [Updated 2020 July; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/ephedra

- CAB. Appendix e: examination single herb list. Sacramento: CAB. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.acupuncture.ca.gov/students/herb_list.pdf

- CAB. Appendix f: examination herbal formulas list. Sacramento: CAB. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.acupuncture.ca.gov/students/formula_list.pdf

- NCCAOM. The Chinese herbology content outline: effective January 1, 2020. Washington DC: NCCAOM, 2020. [Update January 2020; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.nccaom.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/2020%20CH%20Content%20Outline%20and%20Bibliography%20Jan%2020.pdf

- Austin S, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Qu H, et al. Acupuncture use in the United States: who, where, why, and at what price? Health Mark Q 2015;32:113-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). Medi-Cal provides a comprehensive set of health benefits that may be accessed as medically necessary. Sacramento: DHCS, 2020. [Updated 2020 July 6; cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal/Documents/Benefits-Chart.pdf

- Gabel JR, Whitmore H, Satorius JL, et al. Collectively bargained health plans: more comprehensive, less cost sharing than employer plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:461-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Specialty Health (ASH). Acupuncture services provided in a specialty provider network setting exceed national benchmarks for patient satisfaction, quality and treatment success. Carmel: ASH, 2016. [Cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available online: https://www.ashcompanies.com/MediaCenter/NewsArticle?newsArticleId=123384

Cite this article as: Suh Y. The regulation of Chinese Medicine in the U.S. Longhua Chin Med 2020;3:17.